Antti Pinomaa, LUT University

Due to Corona virus and covid-19 crisis that reached Europe and Africa in March 2020, the very same week, when the plan was to travel to Namibia and go on site to upgrade the Fusion Grid pilot system to the configuration it should have been from the day one, since 7th December 2019 when the system was first time launched. All and rather long preparations were made in the first weeks of March, bags with goods and components for pilot upgrade were packed, but then just one day before, being 12th March, the departure day, that was Friday 13th, we got information that all the trips to abroad needs to be cancelled. This was a shock and at least I felt personally very empty as all the work basically was just wiped out. Our aim was to take the 4G LTE base station with us and carry it to Namibia to the pilot site, but it with other components reserved for the power system upgrade were left in the suitcases. After cancelling all the arranged flight tickets, car rentals etc. for the trip, I went home disappointed. We anyway had promised to the people in the community that we will come and upgrade the system to a form it should have been from day one.

However, it was not that easily over. Luckily Professor Marko Nieminen from Aalto University was already on his way to Africa, not Namibia, but Tanzania, and he was carrying one of the bags full of system upgrade components. And he, as being there “close” already, kept going to opposite direction, not back to North but South. There were new batteries and power converter connecting all the components, panels, batteries, loads, waiting in Windhoek, Namibia at the warehouse of our local partner who finally had got the components, again which were told to be there already in December. After some struggle with money and funds bank transfers, communication and trust issues etc. Prof. Nieminen was able to get the components to his rental car and he started heading to Oniipa, 700 km up north from Windhoek Tuesday 17th March.

Meanwhile myself together with PhD student Iurii Demidov at LUT had started imaging could the system swap be done jointly remotely and locally, we providing step-by-step instructions to our local maintenance person living in the community electrified by the pilot system, and he discussing and following the steps with local electrician. The work was planned to be done via Skype video connection. Ambitious plan, but we would not want to give up, as Prof. Nieminen was there driving to Oniipa jeopardizing his own health. But what if something goes wrong etc. and then the people there to whom we gave electricity three months earlier for the first time of their lives would be taken away. All these questions and poor risk analysis we decided to go for it.

We got some version of instructions ready Tuesday 17th March and Prof. Nieminen was then that evening arriving to Oniipa. The plan was to do the swap 18th March, and Prof. Nieminen would be there to follow and report the installation progress locally there to us. However, while driving to Oniipa, he as everyone else being abroad got message from Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland to leave the country as soon as possible, as the borders will be closed within next few days. So Prof. Nieminen booked a return flight and was able to got the very last seat of the very last flight departure next evening . We heard this in the evening while remotely guided Prof. Nieminen to update the firmware to the battery according to the instructions we were given, and that was a mistake, we were given wrong info and the battery went to locked mode and during the same Skype call we heard that he could not stay there to follow the system swap, but needed to leave early in the morning driving back another 700 km to catch the last flight. So another set backs but what you do. At least we cancelled the electrician coming to the site at that early next morning as planned, and maybe not at all.

Anyway, next morning 18th March we started at five in the morning before the sunrise, Prof. Nieminen dropped the stuff to site, and told what battery button to button while we from LUT having Skype call to South Africa to the battery manufacturer support person giving him remote access to the PC at LUT, which again was chained via remote access to the PC at site and running the firmware update remotely from South Africa via LUT lab to the site to the battery management system, while telling us and local people at site which button to press, how long and in which order. Somehow that was successful and new firmware was updated to both batteries after few hours. Then we were able to go towards the actual system swap. But had to call the electrician back to the site, as the game was again on!

Elctrician came after one hour, and we started the system swap following the instructions we sent there but perhaps due to the form of instruction, 4-5 pages in pdf and the working aspects of local electrician they did not follow those, basically at all. We had Skype calls between us sitting in LUT lab and our contact person at site via the phone and Sim card we left there every now and then with random interval once per hour and once per few hours. After few errors and wrong moves at site, very long day sitting and waiting at LUT lab waiting for a next call and steps to take the system components were swapped, and somehow we were able to take remote control of the system after new system startup just before the sunset. So lights supplied form the old system, which were switched off in the morning were switched back on in the evening with the new system.

So in the end of the day, the boarders of Namibia were closed, Prof. Nieminen after his second power stage was safely in a plane, and most importantly, even was a risky move, and after a long day filled with full of events, surprises, delays and problems, the spark we lighted up in Oniipa in December2019 , a day after Finnish independence day was still on then few days before Namibian 30th Anniversary independence day, and keeps on going strong still. It was nice to send Prof. Nieminen a message to airplane in that evening that his journey to Namibia was not futile, but was the key thing us being successful in this thread. Obviously, we did our part remotely from LUT, and that was essential action as well to pull it through completely.

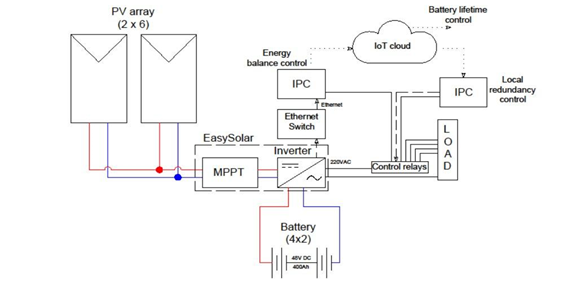

Now as an outcome of these efforts, we have even more stable and reliable smart off-grid system pilot environment in use for research and development of new concepts for years to come.

Maybe the main lesson learned from all this, is that never give up, or do not underestimate the potential and abilities of local community, or yourself, and the tools and new ways of working utilizing and through existing digital and technology platforms we have in use every day. This gives good prospects to the future work and how to approach things differently in these new normal times. You can do things differently, develop new methods, and you should question and evaluate your standard ways of working, frequently. Transition is always present. Don’t stop, but adapt.